Within the massive Quercus genus, oak species are subdivided into a number of sections, though all commercially harvested New World oaks can be placed into one of two categories: red oak, or white oak. This division is based on the morphology of the trees themselves—for instance, red oaks have pointed lobes on the leaves, while white oaks have rounded lobes.

But in addition to the leaves and outward appearance of the trees, the wood of the various oaks also have a few important distinctions. Most notably, white oak is rot resistant, while red oak is not—an important detail for boatbuilding and exterior construction projects. White oak also has a unique ray fleck pattern when perfectly quartersawn that’s seen more often in antiques—a figure that’s sometimes called “tiger oak” in antique furniture circles.

It should be noted that red oak also has conspicuous ray fleck patterns on its quartersawn surfaces, but it’s generally just not quite of the same caliber and size as white oak. (See this quartersawn picture of red oak for reference.)

OAK LUMBER: SUPERFICIAL COLOR DIFFERENCES

While there is one specific wood species (Quercus alba) that’s commonly considered the “white oak,” and there is one specific species (Quercus rubra) that’s considered the “red oak,” when you buy oak lumber within North America, oftentimes you will not actually be buying these two exact species, but instead you may be buying one of the oaks contained within the two broad red and white groupings. Basically, you’re buying characteristics found in an oak group, and not necessarily an exact species. For the rest of this article, I’ll be referring to red oaks and white oaks (plural) as two different groups of trees, and not simply as individual species.

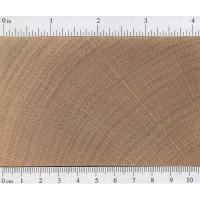

At a casual glance, unfinished oak lumber will generally be light brown, either with a slight reddish cast (usually red oak), or a subtle olive-colored cast (white oak). However, there are abnormally light or dark outliers and pieces that are ambiguously colored, making separation based on color alone unreliable—this is especially true if the wood is finished and/or stained.

Nonetheless, it can be helpful to get a baseline view of the typical color that’s seen in red and white oaks. Listed below are small thumbnails of various oak species in their raw unfinished form, arranged in either the red or white oak grouping. Comparing the two groups is simultaneously helpful and also confusing. You’ll notice that there’s a general categorization of color that most samples fall into (helpful), but you’ll see that there’s also no hard and fast rule to easily tell the two groups apart by color (that’s the confusing part).

RED OAK GROUP

WHITE OAK GROUP

Looking at the examples above, you may notice a loose pattern where red oak species tend to have a slightly paler and redder hue on average, while white oak species have a slightly more olive hue. There are of course outliers and individual variation from tree to tree, so the above grain samples should by no means be meant as an accurate representation of any of the species as a whole.

But realistically, even if you can discern a pattern in the red/olive dichotomy of oak coloration, you can hopefully also see how much overlap and unpredictability there are between pieces.

TIPS FOR ACTUALLY TELLING RED AND WHITE OAK APART

In most cases, we won’t have access to the tree or its leaves, so all we have to go on is the wood itself. Here are some ways of telling types of oak apart that tend to be a little more reliable than using color alone.

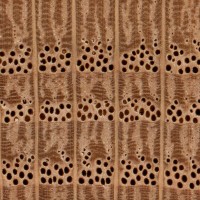

1. LOOK AT THE ENDGRAIN

A quick and fairly reliable way to tell the two oaks apart is simply by looking at the endgrain. In order for this to work, the ends of the board can’t be painted, sealed, or rough-sawn. A freshly cut oak board should be easy to distinguish:

The pores found in the growth rings on red oak are very open and porous, and should be easily identifiable. White oak, however, has its pores plugged with tyloses, which help make white oak suitable for water-tight vessels, and give it increased resistance to rot and decay. The presence of tyloses is perhaps the best and most reliable way to distinguish the two oaks, but it comes with a few caveats:

1.) Make sure that you’ve cleaned up the endgrain enough to see the pores clearly, and blown out any dust from the pores. You don’t want a “false-positive” and mistake sawdust clogged in the pores for tyloses.

2.) Make sure that you’ve viewing a heartwood section of the board in question. While white oak has abundant tyloses in the heartwood, it is frequently lacking in the sapwood section.

One related test regarding porosity is to take a short section of oak and try to blow air through the pores. If you are able to blow anything through it at all, it’s probably red oak. Take a look at this video, where a red oak dowel was used to blow bubbles in water:

One exception to this rule is chestnut oak, which is still considered to be in the white oak group, even though its pores are open like red oaks.

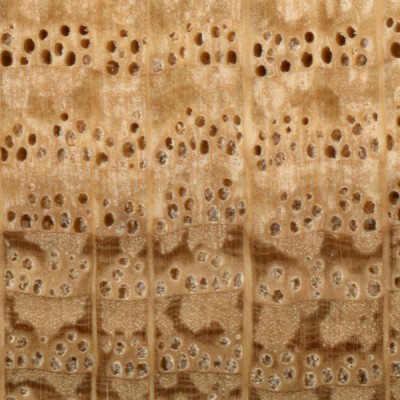

2. LOOK AT THE RAYS

When looking at the face of the board, especially in the flat-sawn areas, you may notice little dark brown streaks running with the grain, sometimes referred to as rays.

Look closely at the picture above, (click on it to enlarge it if you have to), and note the length of the rays in both types of wood. Red oak will almost always have very short rays, usually between 1/8″ to 1/2″ long, rarely ever more than 3/4″ to 1″ in length. (Pictured above on the right.)

White oak, on the other hand, will have much longer rays, frequently exceeding 3/4″ on most boards. (Pictured above on the left.)

This method is probably the most reliable under normal circumstances, and is useful in situations where the wood is in a finished product where the endgrain is not exposed.

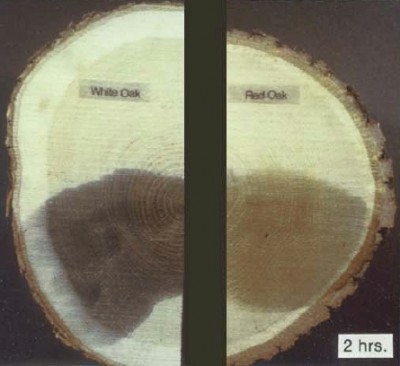

3. USE SODIUM NITRITE

This technique is sometimes used at sawmills if various logs need to be sorted out quickly. Instead of taking the time to analyze each log closely by hand, a 10% solution of sodium nitrite (NaNO2) is sprayed or brushed onto the wood and observed. If it’s red oak, there will only be a small color change, making the wood only slightly darker. But if it’s white oak, there will be a noticeable color change in as little as five minutes, (though it can take longer if the wood is dry, or if the temperature is low). The heartwood of white oak will eventually change to a dark indigo to almost black.

This method is extremely accurate and reliable, though in most instances, it’s probably overkill. However, if you’re ever in a situation where you can’t separate between red and white oak based on anatomy, this method is nearly foolproof. (Though, only the heartwood will bring about the color change, not the sapwood.)

First, you have to obtain some sodium nitrite (NaNO2). You may be able to find some locally through chemical supply stores, but they typically only sell in bulk quantities, making such a small project prohibitively expensive. However, some online retailers have the chemical for sale in much smaller quantities, bringing it into reach of most that are curious about oak identification.

Next, you need to mix up a roughly 10% solution of sodium nitrite by weight. This ratio actually isn’t as critical as it seems: solutions as small as 1% and as high as 20% have all been used with success, but to err on the side of caution, we’ll use the most appropriate quantity recommended.

RECIPE FOR 10% SODIUM NITRITE SOLUTION FOR TESTING OAKS:

- 1 cup water

- 4 teaspoons sodium nitrite

Directions: Stir in sodium nitrite until clear. Clearly label solution to avoid confusion; sodium nitrite is very dangerous if ingested.

All that’s left is to simply brush this solution onto a raw wood surface and wait for a reaction. With dried wood stored at room temperature, this reaction should take about 10 minutes. Red oak will be only slightly discolored by the solution, sometimes developing a slightly greenish hue, while white oak will gradually turn a dark reddish brown, eventually turning a deep indigo to nearly black.

See the progression photos below for a better look. (Also note that around the 8 and 15 minute marks the water begins to evaporate from the surface of the wood, but the color is still present after the wood has dried, as indicative of the 25 minute photos.)

| TIME ELAPSED | RED OAK | WHITE OAK |

| raw | ||

| 1 minute | ||

| 5 minutes | ||

| 8 minutes | ||

| 15 minutes | ||

| 25 minutes |

WHY YOU’D WANT TO TELL RED OAK FROM WHITE OAK

As to the reasons why you’d want to be able to distinguish between the two, most of the answers have been explained above, but I’ll recap:

- White oak is much more resistant to rot, and is suitable for water-holding applications, boatbuilding, outdoor furniture, etc.

- Red oak should only be used for interior pieces such as cabinets, indoor furniture, flooring, etc.

- White oak tends to be more dense, while red oak is a bit lighter and has a more porous and open grain.

- White oak is usually slightly more expensive than red oak.

- White oak has larger and more pronounced ray flecks when perfectly quartersawn and historically has been used more often in antiques than red oak.

GET THE HARD COPY

If you’re interested in getting all that makes The Wood Database unique distilled into a single, real-world resource, there’s the book that’s based on the website—the Amazon.com best-seller, WOOD! Identifying and Using Hundreds of Woods Worldwide. It contains many of the most popular articles found on this website, as well as hundreds of wood profiles—laid out with the same clarity and convenience of the website—packaged in a shop-friendly hardcover book.